1. Read Nancy Loewen's Once Upon a Time: Writing Your Own Fairy Tale two times. The first time, read the fairy tale. The second time, read the tools and notice how they relate to the tale.

2. Choose several of your favorite fairy tales, other than Little Red Riding Hood, to read and enjoy. You can read three completely different tales, or you can choose three retellings of the same tale to compare and contrast. If you choose the latter option, Little Red Riding Hood is fine. 3. Analyze each of the tales, noting on this sheet where you see each of the tools in action. 4. Write your own fairy tale. If helpful, use Loewen's "Getting Started Exercises" on page 29, or you may use the planning sheet here. To see other books in this series, see this post.

Who: Elementary-aged students (The publisher recommends the books for children in grades 3-6.) What: Learn about different types of writing--non-fiction, fiction, poetry, and drama--and the specific elements required for each type; get practice by studying photos, considering the authors' questions about them, and doing exercises and assignments inspired by them. Let me give you the flavor of these books which are written by different women but follow the same structure. Each two-page spread has a focus. In Picture Yourself Writing Non-Fiction, for example, the author focuses on Detailing the Facts, Sensory Details, Unique Comparisons (similes and metaphors), Characters, Dialogue, Plot, Setting, Scene, Purpose and Audience, Point of View, and Bias. She explains, defines, and gives examples on the first page. On the second, she includes a photo with a "Write about It!" prompt. These books include everything students need for independent study. Concentrating on one two-page spread a day will get them through one book every two weeks. If they do this for all four books, they will know the elements of four types of writing and have a collection of their own pieces two months later. If your students do an exercise or assignment they would like to share, post them in the comments or submit them to the Student Showcase.

Note: This assignment is adapted from Writing Fix and written directly to the student. Read an excellent example of showing vs. telling in Roald Dahl's The Twits. It's called "Dirty Beards." (Warning: I expect you will squint your eyes, wrinkle your nose, stick out your tongue, and say, "Yuck" as you read this. I can picture this beautiful face in my mind!)

It begins like this: "As you know, an ordinary unhairy face like yours or mine simply gets a bit smudgy if it is not washed often enough, and there's nothing so awful about that.

But a hairy face is a very different matter. Things cling to hairs, especially food. Things like gravy go right in among the hairs and stay there. You and I can wipe our smooth faces with a washcloth and we quickly look more or less all right again, but the hairy man cannot do that. And ends like this:

What I am trying to tell you is that Mr. Twit was a foul and smelly old man." Now, Mr. Dahl could have just written "Mr. Twit was a foul and smelly old man" and gone on with his story, but he created a very vivid picture in our minds of exactly what he meant by foul and smelly. Which one do you think is better?

I would like you to do something similar. Think of a basic sentence, using a similar pattern. Maybe you want to include two or three adjectives like he did. Then see if you can create a vivid picture for your audience by showing us what those words really mean. You can follow Dahl's pattern here, too, tacking your original sentence on the end.

Actually, there is one more sentence to the chapter, which I didn't include. It says:

He was also an extremely horrid old man as you will find out in a moment. I wonder what he means. I really don't know, since I haven't read the rest of the book. Maybe you can write your own description before reading Dahl's.

If your students complete this assignment, please submit it to the Student Showcase.

| | Do apple seeds dream happily of growing up to be a tree?

How many little fish might see the stone I throw into the sea? | These are questions Marcus Pfister asks in his simple picture book Questions, Questions. Since we know curious children are an endless collection of questions, let's record some of them. Give students a sheet of paper with the title "Questions, Questions." When they ask questions throughout the day, direct them to the paper, where they can write them. Add the questions, one after another, until students have a healthy list. If your students are young, they can write and illustrate their best questions in a mini-book. Assignment accomplished. If they are older, you can expand this assignment, having them follow the example of Pfister whose questions are couplets 14-16 syllables long. Now they will have to figure out how to revise their questions, making them sound poetic with rhythm and rhyme. If your students do this assignment, please include their best questions in the comments!

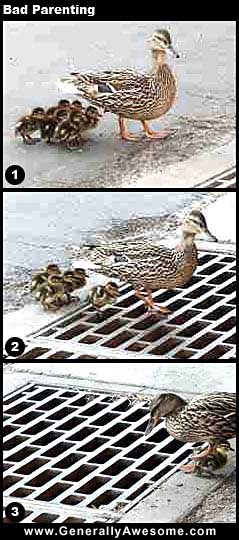

Who: Students of any age What: Write a story based on a series of pictures. I love using these “Bad Parenting” pictures as a writing prompt. The stories students write are generally creative and fun. Prewriting: Invite your students to study the pictures, asking a list of W and H questions—who, what, when, where, why, how—and answering with as much detail as possible, orally or on paper. Note: The teacher need not be the one to think of and ask the questions. Allowing students to brainstorm their own questions is a valuable learning tool as well. Here are some of my questions. - What are the ducks’ names?

- How many ducklings are there in the first frame? The second? The last?

- If the ducks were personified, what would they be saying?

- Where are they coming from?

- Where are they going?

- What is happening outside the borders of each picture?

- What is the weather like?

- When Mama Duck looks in the grate, what does she see?

- What happened before the first picture?

- What happened after the last picture?

- What is Mama Duck thinking?

Once students have studied the pictures and answered their questions, they may be ready to write. Let them. Others may need additional props. If so, you may want to offer graphic organizers to help them see their story develop. Maybe a beginning/middle/end graphic organizer would be useful. This story map or this story map may also be just what they need. Drafting: Once students are ready, release them to capture these pictures in words as creatively and imaginatively as possible. Editing comes later, so they need not be hindered by conventions now. Revising: When the first draft is finished, commend your students but also remind them that there is more work to do. There are many ways to approach the revision part of the writing process and, with time, I hope to include many ideas on this site. For now, let's look at some of Ruth Culham's writing traits: ideas, organization, voice, sentence fluency, and word choice. Choose one (or as many as your students can handle) to address. You will find an excellent starting point with these revision sticky notes here. (Included is one for "Conventions," which you can use for editing.) Publishing: The process is complete; now it's time to celebrate the product. Add it to a collection of other pieces and make a coil bound book. Make a spiffy copy, including the pictures, and share it with Grandma. Send it to me to publish. I just added a Student Showcase to this site!

Who: For students in grades 5-8 What: Using two selections about the same situation--one simple and one more complex--students first notice the differences between them, then write simple and complex pieces of their own. How: Begin by inviting students to read the excerpts from each of the mentor texts below, writing their observations and discussing them. What are their impressions about each excerpt? Which one do they like better? Together, analyze the texts for sentence length, sentence openers, kinds of punctuation, ability to paint a picture in the reader’s mind, point of view, etc. Begin to use showing vs. telling terminology. If you can find the two books in a local library, check them out. Wait to show them until the discussion is complete, so they are not biased by the books themselves. I think they will be amused to see that the first selection comes from an easy reader. When students understand how the two texts differ, give them one of two tasks. Option #1: Rewrite the two selections, developing the simple one and simplifying the complex one. Option #2: Write two similar scenes, one that simply tells about the scene with short sentences and sparse details, the other that shows the scene with varied sentences and rich details. When students have completed their drafts, ask them to share highlights from their simple and complex pieces. Which one do they prefer? Which one was easier to write? Draw boxes around each sentence. How do the widths of the boxes compare from one piece to the other? Highlight the sentence openers. Is there variety? What is their strongest detail? Allow time to revise and edit the pieces before putting them away. (And consider sending me the pieces to add to my Student Showcase!) Selection #1 From I Am Rosa Parks by Rosa Parks with Jim Haskins “One day I was riding on a bus. I was sitting in one of the seats in the back section for black people. The bus started to get crowded. The front seats filled up with white people. One white man was standing up. The bus driver looked back at us black people sitting down. The driver said, ‘Let me have those seats.’ He wanted us to get up and give our seats to white people. But I was tired of doing that. I stayed in my seat. This bus driver said to me, ‘I’m going to have you arrested.’ ‘You may do that,’ I said. And I stayed in my seat. Two policemen came. One asked me, ‘Why didn’t you stand up?’ I asked him, ‘Why do you push us black people around?” Selection #2 From Rosa by Nikki Giovanni “Rosa settled her sewing bag and her purse near her knees, trying not to crowd Jimmy’s father. Men take up more space, she was thinking as she tried to squish her packages closer. The bus made several more stops, and the two seats opposite her were filled by blacks. She sat on her side of the aisle daydreaming about her good day and planning her special meal for her husband. ‘I said give me those seats!’ the bus driver bellowed. Mrs. Parks looked up in surprise. The two men on the opposite side of the aisle were rising to move into the crowded black section. Jimmy’s father muttered, more to himself than anyone else, ‘I don’t feel like trouble today. I’m gonna move.’ Mrs. Parks stood to let him out, looked at James Blake the bus driver, and then sat back down. ‘You better make it easy on yourself!” Blake yelled. ‘Why do you pick on us?’ Mrs. Parks asked with that quiet strength of hers. ‘I’m going to call the police!” Blake threatened. ‘Do what you must,’ Mrs. Parks quietly replied. She was not frightened. She was not going to give in to that which was wrong.”

I saw this idea when I was at a school, the finished stories hanging on the bulletin board in the hallway. So simple and creative! Who: Appropriate for any age but particularly for students who need a little structure for security What: The student uses each letter of the alphabet to tell a story. Let me show you; it will be easier. The following example is the beginning of my youngest daughter's retelling of "The Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf." She created this when she was five. A long time ago there lived three little pigs and their B eautiful mother named C atherine.The three little pigs were named D avid, Danny, and Doug. While they were E ating bacon and eggs and F ried potatoes, their mommy said, "You need to G o out in the world and build a H ouse for all of you." So the three little pigs set off. While they were walking, they saw a penguin with a wheelbarrow full of bricks. "Please, may we have some bricks to build a house with?" "Certainly," said the penguin. I t was hard work building the house, and they made a ping-pong table for all of them to play with. Sorry to leave you in suspense, but you get the idea. : ) What happened when she got to X? She used the word e Xcitedly to begin her sentence. Problem solved! Rebekah's story was eventually typed, illustrated, and preserved in a white hardbound book. Now it's on the shelf, a reminder of her personality and skills at age five and a benchmark of how far she has come!

Other Related Ideas: - One year I wrote our family Christmas letter with this format.

- With this structure, your student could retell a historical event or highlight a person she is studying .

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed