Do you want books to help your students...

...learn the elements of literary analysis?

...study different genres?

...improve their reading and writing skills?

I recommend Nancy Loewen's Writer's Toolbox series. So far, there are nine:

- Action! Writing Your Own Play

- It’s All About You: Writing Your Own Journal

- Just the Facts: Writing Your Own Research Report

- Make Me Giggle: Writing Your Own Silly Story

- Once Upon a Time: Writing Your Own Fairy Tale

- Share a Scare: Writing Your Own Scary Story

- Show Me a Story: Writing Your Own Picture Book

- Sincerely Yours: Writing Your Own Letter

- Words, Wit, and Wonder: Writing Your Own Poem

These books accomplish a lot. First, many of them include a stand-alone story. In Once Upon a Time, for instance, Loewen retells "Little Red Riding Hood." The story can be read and enjoyed all by itself. But then she adds blocks to most pages which explain the tools necessary for that particular genre. Again, in Once Upon a Time, Loewen shows that fairy tales need setting, characters, plot, dialogue, warnings, magic, greed, tricks, secret, repetition, mistakes, problem-solving, and a pleasing end. Phew! That sounds like an overwhelming list, but she keeps the descriptions brief, and she positions the story, so that it illustrates each tool she is explaining. At the end of the books, she reviews the tools, gives "Getting Started Exercises," shares "Writing Tips," and directs readers to a Fact Hound site which lists related books and websites. There's no lack of nourishment for your language arts menu here. Focus on one book a month or intersperse a few of them with the other language arts activities you are doing. Whatever you choose, I'm pretty sure you'll leave the table satisfied. For an additional idea, see the assignment in Inspiration.

"Writing the first draft was a tedious ordeal for me (and still is), but revising was like solving a puzzle: move this sentence, cut this paragraph, change this word, summarize this, stretch that—the challenge of revision was what writing was all about." ~ Nancy Loewen, children's author

A friend sent me this link. (Thanks, Cynthia!) Be encouraged as you set your goals for the new year!

Writing is scary. According to Denise J. Hughes, we can overcome our fear with one word. Find out what it is here. What do you think? How have you begun, or what is your plan to begin?

This afternoon I uncovered notes from a presentation I made at a local homeschooling fair in 2005. Maybe they will be helpful here. (If you make it to the end, there will be a treat!)

Fanning the Flame: Teaching Writing to Your Elementary-Aged Child

Education is not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire.

~ W. B. Yeats

Extinguisher #1

Replace real writing with a list of things to do (penmanship, spelling, vocabulary, grammar exercises).

Fanning the Flame

Encourage your child to write, write, and write some more.

Extinguisher #2

Limit children to certain types of writing.

Fanning the Flame

Allow your child to show her personality, to develop her writer's voice, to write about subjects which interest her. Extinguisher #3

Make writing a separate subject.

Fanning the Flame

Integrate writing with other disciplines. Extinguisher #4

Expect a piece to be immediately perfect.

Fanning the Flame

Encourage your child to utilize the writing process.

Extinguisher #5

Assume that every piece must be a finished piece.

Fanning the Flame

Allow some pieces to remain in the drafting stage.

Extinguisher #6

Insist that a child complete the entire process without assistance.

Fanning the Flame

Encourage, brainstorm, take dictation, type...be helpful. Extinguisher #7

Bring the school mentality home and grade or red mark the child's work.

Fanning the Flame

Appreciate the child's accomplishments. Take note of errors for future instruction. Extinguisher #8

Ignore writing because you feel incapable.

Fanning the Flame

Be a learner. Ah, you made it...or you cheated and skipped here for the treat. Whatever the case, here it is, the story of a boy-turned-author whose early teachers were "extinguishers" and whose later teachers were "fans." Enjoy.

If you have a boy who loves Legos and needs encouragement to write, check out this download which links the two. There is also one that links Legos and language arts here.

The goal in teaching language arts is to improve a student's ability to listen, speak, read, and write. Tucked in the fine print are skills which include at least the following: - Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Spelling

How do you ensure you cover these skills with your students?One way is to buy a workbook, one for each skill, one for each kid, and assign pages. If they faithfully do a page or two a day in each book, they will likely advance to the next level by the end of the school year. Advantages: - Mom and students know exactly what is required each day.

Disadvantages:- Boring!

- It's easy to get bogged down with the habit of filling in paperwork, forgetting that there is an ultimate goal of learning!

- Nothing is really required of the student, other than perseverance.

- Students don't take pride in their work.

- After all those pages are completed, what then? The books likely end up in the trash.

Maybe I'm biased, but those lists are painfully lopsided. What is another approach to achieve the same goal? How about learning the skills in context? When my girls were little and many of their little friends were filling in their workbook pages, my girls were writing. Writing in portfolders. Writing in blank books. Writing stories. Writing journal entries. Writing. Writing. Writing. They were also reading. Reading fiction. Reading non-fiction. Listening to me read fiction and non-fiction. Reading. Reading. Reading. How did they learn spelling, vocabulary, and grammar? They learned these skills through reading and writing. As they read--and heard me read--quality literature, they absorbed new vocabulary, proper grammar, and correct spelling. As they wrote, they applied what they absorbed, refining their understanding on assignments in which they were personally invested. They learned early that writing is a process, that their first draft is rarely their last. Advantages:- Students get to think.

- Creativity can leak out in all directions.

- They have final products they can celebrate and share with others.

- They are motivated because they have a goal in view.

- Because they are able to express themselves, they realize they are a vital part of the learning process.

- The teacher can inspire a love of learning.

- Students learn how to learn.

- One assignment can serve a range of ages and abilities.

- Supplies are simple and inexpensive: paper, pencils, and time, although a computer does make revisions easier.

Disadvantages:- Mom may have to think of or find ideas to spark creativity.

- If students are used to filling in pages, they may initially resist having to think and create.

- If Mom doesn't feel comfortable giving feedback, she may need a writing mentor to help her students.

Again, I may be biased, but I like that list better! The moms of my girls' little friends feared a couple of things about ditching their workbooks: one was possible gaps; the other was standardized tests. Through a methodical system, your students may be exposed to every jot and tittle of every skill, but when you isolate the skills from real life learning, do children actually know how to apply them? From what I have read and seen firsthand, the answer is usually no. In my first classroom experience, my eighth graders came to me engorged from a steady diet of grammar instruction the prior year. I was happy because I could feed them something different. We could work on writing, incorporating grammar instruction as needed. What I quickly discovered was that, despite learning from an excellent teacher, not only did the kids still not understand or remember the grammar they had learned from her, they also didn't know how to write. Even in a traditional classroom setting, these kids had huge gaps.And testing? At least in our case, my girls have always tested very high in language arts. Through consistent drafting, revising, and editing, they learned the nuts and bolts of the English language and were able to choose the best answer on the test most of the time.I know writing is on the top or toward the top of most homeschooling moms' I'm-not-sure-I-can-do-that-well list. If that describes you, you're the one who is inspiring me to build this site post by post. I want to give you concrete writing ideas, tips, and resources to ensure you're covering the whole language arts package. If you need a few workbooks for security, it's okay, but I encourage you to step out and give real reading and writing a whirl. Because it's fun, you may fear you're missing something, but let me assure you: you're nurturing thinkers, students who can confidently listen, speak, read, and write. With those tools, think of what your kids can accomplish!

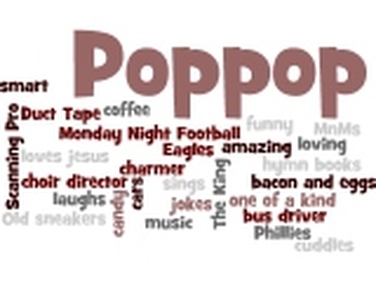

Play with words this summer. Make a Wordle Word Cloud. My middle daughter made one for her grandfather last year. She framed it and gave it to him for his birthday.

When I read Ruth Culham's 6 + 1 Traits of Writing this past weekend, I noticed something new. She claims that, although it's okay to end sentences with other parts of speech, ending them with a noun makes them more powerful (201). She illustrates her premise by revising a proverb: A rolling stone gathers no moss. (noun)

If a stone rolls, hardly any moss will be gathered. (verb)

If you are concerned about moss gathering on a stone, roll it. (pronoun)

When trying to rid yourself of moss, roll the stone quickly. (adverb)

If you roll the stone, the moss will become smooth. (adjective) Hmmm, interesting. I'll try it here, ending my sentences with a noun to see if they are more powerful. Here I go. When I read Ruth Culham's 6 + 1 Traits of Writing this past weekend, I noticed a new tip. She claims it is more powerful to end a sentence with a noun rather than another part of speech. She illustrates her premise by revising a proverb. A rolling stone gathers no moss. (noun)

If a stone rolls, hardly any moss will be gathered. (verb)

If you are concerned about moss gathering on a stone, roll it. (pronoun)

When trying to rid yourself of moss, roll the stone quickly. (adverb)

If you roll the stone, the moss will become smooth. (adjective) Hmmm, interesting thought. I'll try it here, revising my sentences to ensure I end each one with a noun.

My experiment here is too short to confirm or deny her suggestion, but one thing I can say: this would be an interesting way to get a student to rethink/restructure (i.e. revise) her sentences. Ask her to end several sentences in a paragraph with nouns and see how it changes her paragraph.

Have you seen this advice before? Do you think about it when you write? What have you discovered?

Over the weekend, I found 6 + 1 Traits of Writing by Ruth Culham at the thrift shop. For $2.50, I couldn't let it stay on the shelf. This paragraph from Culham rang true for me.

When I was in school, the papers that got the highest grades held the reader at a safe arm's length. They tended to pontificate. I remember being told never to express a personal opinion unless asked. And never use 'I,' which was always tough to figure out: Who else did the reader think was writing the piece if not 'I,' after all? My assigned readings, however, were passionate, opinionated, stylistic, and fascinating. But when it came to my own writing, on went the straitjacket, and I wound up pumping out stuff that was stilted, cold, and distant. It was boring--but it always got high marks. Unfortunately, this tradition is still alive in many of the classrooms I visit. And more than likely, something that's boring to read was boring to write. It will be nearly impossible to get students engaged in writing if all the excitement's been drained out of it (103).Why is it that students are so often shoehorned into five-paragraph, formal, voiceless writing? It's easy to teach a formula. It's easy to grade a formula. It's easy to keep control of the process when you have a classroom of kids. The question: why? The answer: easy.The result: boring!It happened to me as a student. The result was that I thought I had to use big words and sound like something I wasn't. Stilted, cold, and distant didn't describe me as a person, but they certainly described my writing. Sadly, the habit went deep; I still fight to get out of the ditch I thought was mine. I want to give my students something far better. I want them to be free to experiment, to create, to be themselves. I don't want to jam them into a specific style, draining the excitement out of writing; I want them to discover that they have something to say, and they can say it well with their own voice. They can be the ones writing passionate, opinionated, stylistic, and fascinating pieces. What can we do to make writing more exciting for our students?- Let them choose their own topics.

- Don't lock them into one format (i.e. the five-paragraph essay). Allow them to experiment with different genres.

- Give them a reason for writing that goes beyond the teacher and a grade, offering assignments and projects that captivate their attention.

- Integrate writing into everything they do rather than relegating it to worksheets.

- Remember that writing is a process. Editing is one part of the process; it's not the focus. It's important for published pieces to be correctly spelled, capitalized, and punctuated, but if mechanics are the primary focus during the process, a student can end up with a correct, but lifeless, paper. (That described my writing, too.)

- Look at writing you enjoy. Do any of the pieces follow the five-paragraph format? Does every paragraph have a topic sentence? Does every sentence have a subject and a verb? Likely not. Invite your students to look at writing they enjoy, observing it closely and imitating it.

It is true that you invite risk when you walk away from formulaic writing assignments, but you also welcome creativity, thinking, and passion. Instead of reading a predictable piece that you will soon forget, you will likely read one that comes from the heart, leaving a mark on yours.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed